What is gastroparesis?

Gastroparesis means “paralysis of the stomach.” It is a digestive motility disorder in which the stomach muscles, controlled by the Vagus nerve, fail to contract and move food from the stomach into the intestines at the proper rate. Under normal conditions, the stomach stores food only long enough for it to be ground down into small pieces by contracting stomach muscles in preparation for further digestion in the intestines. This process is slowed in those with gastroparesis, resulting in food being “stored” in the stomach for an abnormally long period of time.

What are the symptoms of gastroparesis?

Gastroparesis is marked by one or more of these symptoms:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Bloating/Distension

- Early Satiety

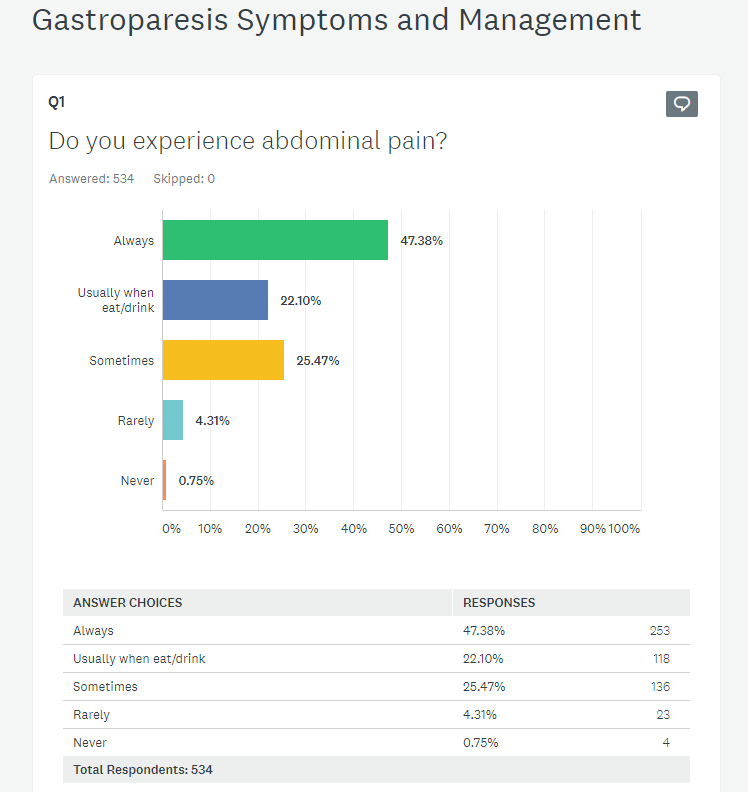

- Stomach/Abdominal pain

- Gerd/Acid Reflux

- Weight Fluctuations (Loss/Gain)

What are the complications which can result from gastroparesis?

Complications of gastroparesis may include:

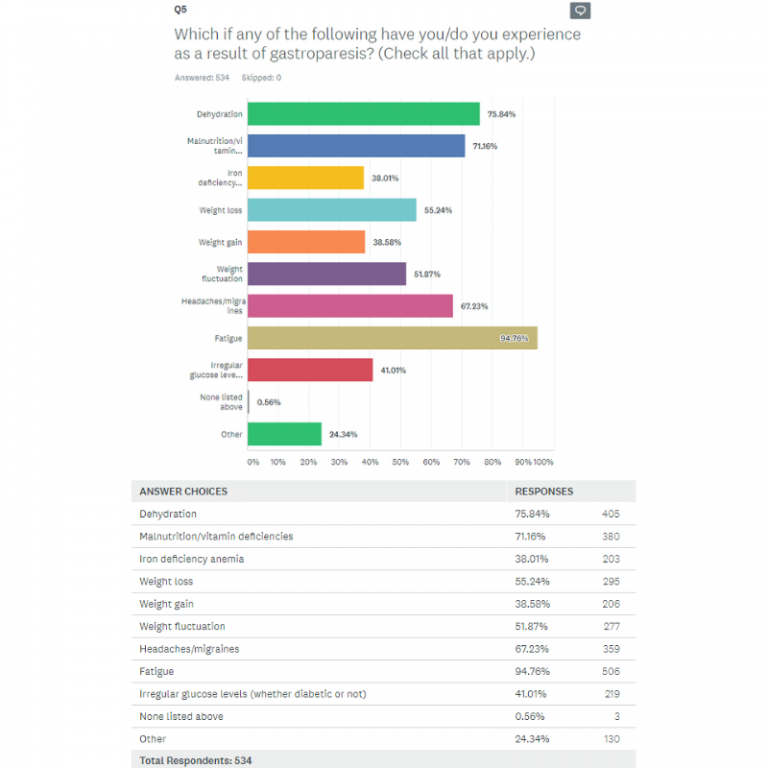

- Erratic Blood Sugars

- Chronic fatigue

- Esophageal Damage

- Bezoars/Intestinal Tract Blockages

- Dehydration

- Malnutrition

How is gastroparesis diagnosed?

Gastroparesis is most commonly diagnosed by the Gastric Emptying Study (GES), a procedure in which radioactive material (food) is traced by a scanner as it moves through one’s digestive tract. This test allows one’s doctor to track the rate at which food travels from the stomach to the small intestine. Other methods of diagnosis include upper endoscopy, barium x-rays, gastric manometry, and the wireless motility capsule (Smart Pill) which, when swallowed, transmits data regarding the rate of passage through the digestive tract.

Though the Gastric Emptying Study is still considered the “gold standard” of diagnosis, there are issues and limitations associated with this study, as it is simply a snapshot of a moment in time. Test results can vary widely over time , and so, it is not uncommon, for example, for one test to show severe delay and another follow-up study to show mild delay or even normal emptying rates. Consuming the recommended standardized meal, tracking emptying rates for 4 hours (rather than the 90-minute or 2-hour tests offered by some facilities), testing for both a delay in solids and in liquids, and stopping all medications which could interfere with the results (as directed by your physician) can help to produce the most accurate emptying measures.

Diagnosis can be difficult even under the best of circumstances. Some patients find they experience “flares,” or periods of severe symptoms, followed by relatively symptom-free days, and, so, the timing of doctor visits and testing might be a factor in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. And to complicate the situation further, symptom severity does not necessarily correlate with the rate of emptying, resulting in some patients with severely delayed emptying having only mild symptoms and others with minor delays in emptying experiencing quite severe symptoms. In addition, symptoms often overlap with or mimic other conditions (such as functional dyspepsia or IBS). Diagnosis should, then, be based on a number of considerations, including test results, patient symptoms and history, and the elimination of other possible symptom causes.

What are the causes of gastroparesis?

Common causes of gastroparesis include:

- Idiopathic (no known or easily identifiable cause)

- Diabetes

- Vagus Nerve Damage

- Connective Tissue Disorders

- Autoimmune Disorders

- Neuromuscular Disorders

- Certain Types of Cancer/Cancer Treatments

- Viruses

- Some Medications

What are the common treatments for gastroparesis?

There are variations in symptoms and levels of severity of gastroparesis, and individuals respond differently to the available treatment approaches. In general, patients struggle to maintain nutrition levels and are at risk of malnutrition and/or dehydration due to their inability to ingest and absorb nutrients. There is no scientifically-known cure for gastroparesis, and, so, treatments tend to focus on symptom control and may gradually progress to greater levels of intervention, based on how well or poorly one responds to each step in the treatment plan.

Treatments may include:

- Dietary Changes

- Medications

- Alternative Therapies

- Tube Feedings or TPN

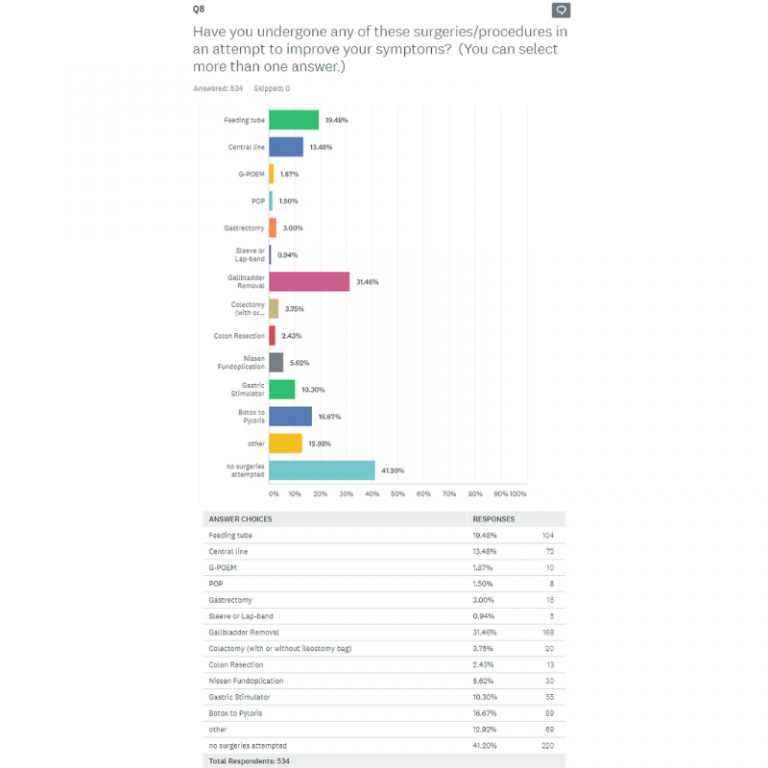

- Gastric Stimulator and/or Other Surgeries

The basic GP diet calls for small, frequent, low-fat, low-fiber, high-protein foods and liquids (at tolerable levels) which are easier to digest. Many diet plans call for a 3-step process, beginning with a liquid-only diet and then progressing to soft-foods (low-residue, low-fat), and eventually, a maintenance diet (which adds just a bit more fat as well as some well-cooked, easy to chew foods).

In reality, many find the basic diet plan difficult to follow, as tolerances vary, and it must be tailored to fit individual needs. In short, what works for one might not work for another, so it is largely a process of trial and error. To complicate this further, many of us find that our food tolerances can change from day-to-day and over time. So, what works for us one day might not work the next.

Some find they get “stuck” on one “step” in the diet or that they move up and down the steps rather than steadily progressing. Others find that, though they follow the plan precisely, they have little to no tolerance of the recommended foods and liquids and cannot maintain adequate hydration and nutrition levels.

When this is the case, medications such as prokinetics and antiemetics may be helpful. But some must also resort to methods which provide supplemental nutrition, such as feeding tubes and TPN (intravenous feeding).

We recommend keeping a food journal which notes your daily intake and any reactions, intolerances, or worsening symptoms you experience. This might assist you in finding patterns over time. Further, we suggest “testing the waters” by slowly and gradually adding one or two liquids/foods, in small amounts. Be mindful of the guidelines and note what works for others, but do not be surprised if your tolerances differ from those of others, and be willing to tailor the diet plan to suit your individual needs. You must do what works best for you!

If you find you are not maintaining adequate hydration and nutrition levels, consider asking your doctor for a referral to a dietitian or speak with your provider about the possibility of other methods of supplementation.

[See: https://med.virginia.edu/ginutrition/wp-content/uploads/sites/199/2014/04/Gastroparesis-and-DM-02.23.17-1.pdf and http://www.arizonadigestivehealth.com/gastroparesis-diet/ for guidelines and sample diet plans.]Is gastroparesis common?

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), an estimated 5 million people or more live with gastroparesis; yet, this illness is still little-known to the public and often misunderstood by healthcare professionals who impact our care. This lack of knowledge can lead to under-diagnosis and/or delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Is gastroparesis progressive?

Gastroparesis can be but is not necessarily progressive. Some patients improve over time, while others find their condition worsens. Some note little to no change in their symptoms or severity level over time. Many patients experience fluctuations between (sometimes lengthy) symptom-free, remission-like periods and symptom-heavy flares.

Progression depends largely on the cause and on how well one responds to dietary changes and available treatments. In some cases, treating the underlying cause (such as Diabetes), can lead to significant symptom improvement. In other cases (such as post-viral gastroparesis or gastroparesis brought on by medications), the scientific literature indicates the condition can (but not necessarily will) resolve itself over time.

Regardless of severity level, cause, or pattern, there is no scientifically-known cure for gastroparesis and no one treatment which benefits all. Progression and effectiveness of treatments are highly individualized.

Is there help for me?

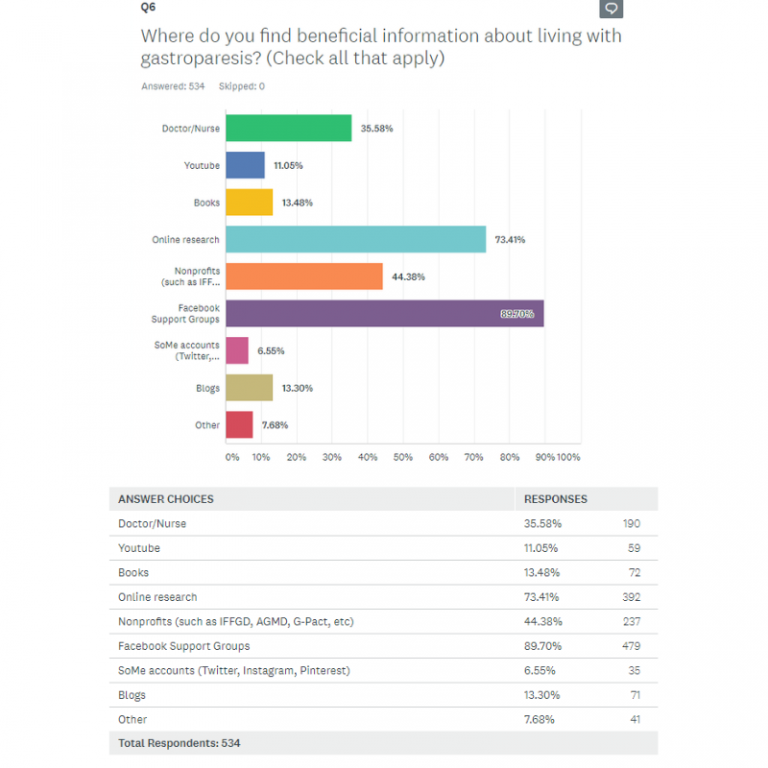

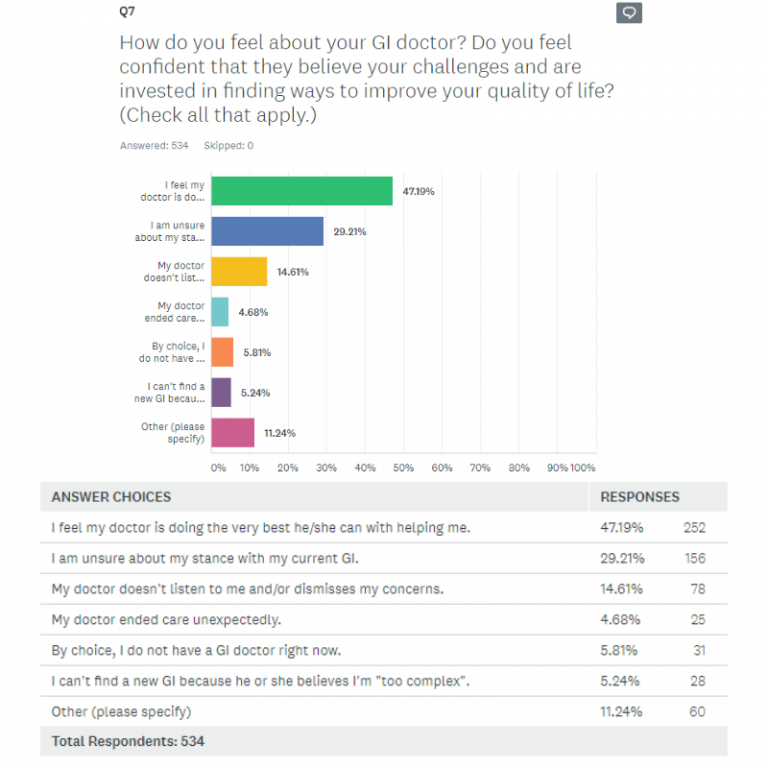

There are many sources of help to which you might turn. Our “Resources” section includes a list of our various support groups, blogs, social media links, and other credible sources of information which will assist you in this regard. In addition, we are always happy to hear from you and will gladly answer your questions and/or assist you in finding additional resources. You can reach us through the contact form on the website or via e-mail at info@curegp.org.

*Please note that any recommendations offered are opinion only and cannot substitute for professional medical advice. Please consult your medical team for proper individualized care.